It hurts when I see the people I love bleeding tears. The only thing that comforts me is the fact, that we are Palestinians. Being a Palestinian means that we have strength in spite of injustice, hope in spite of the misery, and smiles in spite of pains.

It hurts when I see the people I love bleeding tears. The only thing that comforts me is the fact, that we are Palestinians. Being a Palestinian means that we have strength in spite of injustice, hope in spite of the misery, and smiles in spite of pains.

Escaping from final exams pressure, I went to a wedding with my sisters. Everyone around me was smiling, clapping and dancing for the bride and the groom except for me. My smile turned into tears.

I incidentally met an old friend, from whom I had not heard anything since the ninth grade. We had been in the same class until I moved to another school. I was so happy to see her after five years. However, her situation made me feel sad.

As I greeted her, I noticed an innocent, cute child playing in front of us. “This girl is my daughter.” My friend said with a smile. “Are you joking?” I gasped. “You are only 18 years old!” I couldn’t believe my eyes. She was a mother of a two-year-old girl! I tried to pull myself together in order not to show how surprised I was. “When was your wedding? Are you happy?” I asked.

“Thank God, I am bringing up my daughter alone,” she said. I kept silent but I am sure my face’s features showed my astonishment. Many thoughts filled my brain. I was thinking if she had broken up with her husband, or if had he left her alone and travelled. I waited for her to continue because really I couldn’t speak then expecting bad news. Suddenly, she got out her wallet and showed me her husband’s picture. “Isn’t he handsome? He is not alive anymore; he was martyred,” she said proudly.

It took me quite long time to understand that she is a widow at such a young age. I didn’t say a word. I felt helpless because I was sure that her sorrow was too deep. Yet, she hid that behind the smile of pride. “How was he martyred?” I asked.

“Two years ago,” she answered with shining eyes, I felt the tears were trying to fell from her eyes but not a tear in sight. “He was in Biet_Hanoon, visiting a friend, when suddenly a rocket shelled an empty area close to him and he was one of the victims. Israel justified this with a trivial excuse as usual, seeing that the empty area is the place where resistance groups trained.”

Just looking at her red eyes following her daughter was killing me. I was bewildered. What was his fault to die in the age of twenty-three after a week of his daughter’s birth? And what is her guilt to deserve being a widow leading hers and her life alone with her daughter? I believe that it’s their destiny, but it’s really a hard one to accept. However, she had. She buried her sorrow and for her daughter, played both the role of mother and father.

I realized that the miserable Palestinian life has some good aspects. It creates iron people able to lead their lives no matter how tough the going gets. That’s why now; I am not surprised that I met my friend at a wedding. Israel has to know that we are strong enough to handle anything no matter how hard it is. In Palestine, Life goes on despite the sorrow.

July 8, 2010 | Categories: Life in Gaza, Reflections and memories | Tags: Gaza, Gaza siege, IOF, Israeli Occupation, Martyrs, Palestine | 11 Comments

I am a third-generation refugee, born and raised in one of Palestine’s largest refugee camps, Jabalia, originally from Beit-Jerja village, my grandparents’ evergreen home which they had to flee under Israeli fire in 1948.

I am a third-generation refugee, born and raised in one of Palestine’s largest refugee camps, Jabalia, originally from Beit-Jerja village, my grandparents’ evergreen home which they had to flee under Israeli fire in 1948.

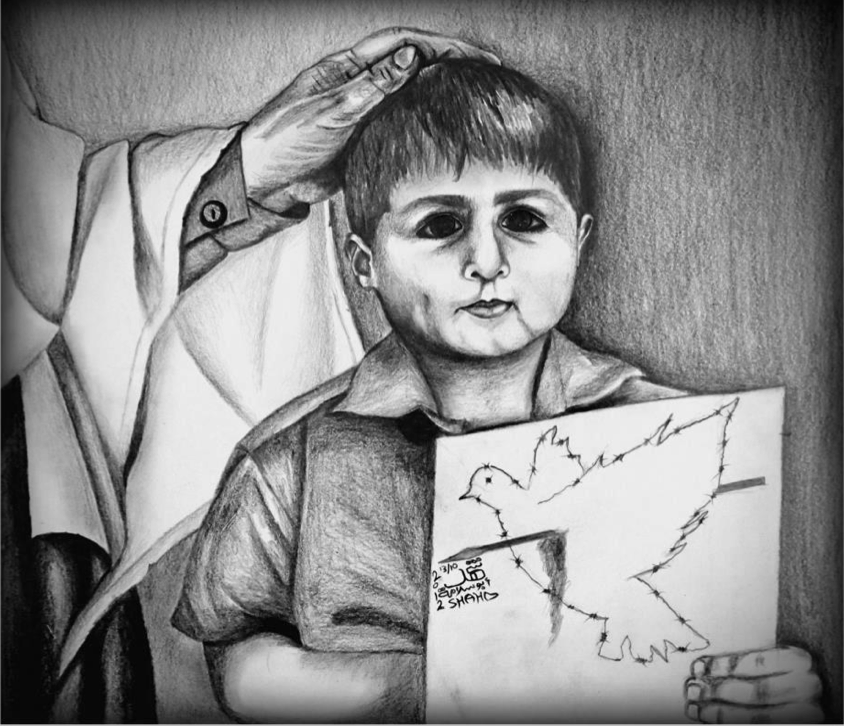

I was born a survivor- my mother’s labor occurred during a curfew that Israeli military forces imposed on Jabalia Refugee Camp from which first intifada erupted a few years earlier. While fearing for her life and her yet-to-be-born child, she walked through Jabalia refugee camp’s alleys, leaning on my grandmother who held a white piece of cloth in one hand and a lantern in the other, hoping for mercy from the Israeli soldiers who were indoctrinated to shoot ever moving being. Our family home then was one-kilometre away from the UNRWA clinic in Jabalia. There was no ambulances, no phones, and the whole neighbourhood was under blackout. “While pointing their guns at us, unscrupulous Israeli soldiers obstructed our way,” my mum recalled, “They harassed and interrogated us even though I could hardly stand.”

My mum’s memories of the day of my birth cannot easily be forgotten. My father couldn’t be around around her as an ordinary husband. The thirteen years of suffering that my father spent in Israeli jails were not enough for those terrorists. My dad had been sentenced to seven lifetimes plus ten years, but thankfully, he was released in the 1985 prisoner exchange after serving ‘only’ thirteen.

My father was born 4 years after Nakba to dispossessed parents in Jabalia Camp where refugee families survived on nothing but the dream to return. He was 15 when the Gaza Strip alongside the remainder of Palestine fell under the Israeli military occupation in 1967, and when he spent his first 2 months in jail as a child prisoner. At the age of 19, he was sentenced to seven lifetimes plus ten years. Each life sentence for a Palestinian equals 99-year-prison-term. Had he not been released in the 1985 prisoner exchange, he could have spent a total of 703 years in Israeli jails – my mother, my siblings and I would have been a dream buried alongside him in jail – a horrifying thought that haunts hundreds of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli custody.

In fact, my dad was never free. He was restricted in his movements and always anticipated his house being vandalised to rearrest him. They deprived him of the basic right of a husband, sharing with his wife some of the most difficult and intimate moments of pregnancy. She brought me into this life, where safety, freedom, and justice are denied. Assisted by my grandmother, she returned home as soon as she recovered so my father could hold me. They defiantly celebrated my advent, but in Palestine no smile could ever last.

”In the middle of the night, a month after your birth, a huge force of armed Israeli soldiers suddenly broke into our home, damaging everything before them,” my Mum recalled. “They attacked your father, bound him with chains, and dragged him to the prison, beating him the whole way.” The happiness of the new baby – me – didn’t continue for the whole family. My mum could breastfeed me until then; her grief ended her lactation.

My dad was held for six months under administrative detention, without any charge or trial, an arbitrary procedure that Israel has used against tens of thousands of Palestinians since 1967. Prior to this time, my father served this term two times during my mum’s pregnancy with my elder two siblings Majed and Majd. Although one can hardly find a positive side to their traumatic experiences, they used to amaze me by the jokes they made around my mum not needing to go on birth control, because my dad’s detention acted as such.

The day my father got his freedom back, six months later, my mum was awaiting him as if she knew he was coming. He couldn’t believe how big I was after seven months: he couldn’t stop hugging and kissing me for even one second. That time was the last time my father was taken away from him family, but my parents never stopped worrying over the future of their children whose safety they couldn’t guarantee under the Israeli colonial occupation.

Writing about my childhood experience brings a lot of tears, especially that this story is common across Palestine. Every Palestinian child is convicted to a life of uncertainty and oppression without having to commit a crime. Being a Palestinian is our only offense.

Two years after my birth, the Intifada of stones ended marked with celebration of victory and illusions of autonomy which the Palestinian National Authorities brought after signing the Oslo peace process with Israel in 1993. But this happiness or illusion, yet again, didn’t last. Another Intifada began in 2000, declaring the death of Oslo which acted as a cover for further Israeli dominance over Palestinian lands and lives. In 2000, I was 9 years old stuck with children of Palestine in a seemingly never-ending cycle of violence.

In Palestine, no smile can last as long as Israel carries on acting with impunity. However, In Palestine, no one seems to give up dreaming of a brighter future for Palestine, in a just peace that will guarantee us with freedom, justice, dignity and return

June 7, 2010 | Categories: Life in Gaza, Stories from my father's life | Tags: Administrative detention, Gaza, IOF, Israel, Israeli Occupation, Israeli Prison Service, Jabalia Camp, Palestine, Palestinian Political Prisoners | 33 Comments

Palestinians were waiting on fire for the Freedom Flotilla– the vessels that were carrying seven hundred Turkish, some people from different nationalities. Those ships were coming to Gaza carrying 10,000 tons of humanitarian aid to Gaza. Although they were on the international waters they have been attacked by Israel forces. However, nothing that Israel does is surprising. Israel stormed and attacked those vessels violently and prevented them from continuing their pure humanitarian work they were intending to do.

They continued creating trivial excuses for their ugly crimes. Israel said that those ships were not only for providing aid, but also it was an act of provocation. However I need an explanation, will it be reasonable to kill up to nineteen people and wound more than thirty for this reason though? I can’t understand, are they really humans?

Here in Gaza, public strike is announced. Protests are spread in every street. The Palestinian people ignored their differences, including their political point of view, to be one force to express their rejection of the ongoing aggression against them, and declare their solidarity with their brothers in all the countries who were martyred and were injured this morning while marching in the Freedom Flotilla to break the siege on Gaza.

On behalf of all Palestinians, I say thank you for everyone sacrificing to break Gaza siege. We are all proud of those people who insisted to support Gaza even they were threatened by Israel.

May 31, 2010 | Categories: Life in Gaza | Tags: Flotilla, Gaza, Gaza siege, IOF, Israel, Israeli Navy, Israeli Occupation | 1 Comment

My parents Ismail and Halima

On 21 May 1985, my father Ismael regained his freedom, after being in the dark of Israeli prisons for 13 years.

“I was sentenced for seven lifetimes plus 10 years and I thought that Nafha Prison would be my grave. Luckily I didn’t stay that long there, and I was set free to marry your mother and to bring you to this life,” my father playfully said while my mind struggled to understand his underestimation of such an experience that is inconceivable to most. His reference point was, however, different. It is only “not that long” if compared to the original sentence to which he was bound if the deal to exchange Palestinian and Israeli prisoners didn’t proceed.

I can’t recall my Dad ever showing any regret or sorrow for the precious years of his youth that were stolen from him. He turned his prison experience into a song of life. He believes that it is the reason behind his solid principles, his strong character, his intimate friendships, and his emancipatory perception of life.

I’ve always been proud to be his daughter, and I’ll always be. He is a revolutionary to whom revolutionary thinking is an organic part of his upbringing as a Palestinian refugee. My father was born to a dispossessed family from Beit Jerja, 4 years after Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948, an event we call Nakba (Catastrophe). He was born in Jabalia refugee camp where minimal means of survival did not exist, and Israeli oppression defined their daily lives with a defiant form of resistance.

“The Triumphant Power of Revolution”

As a 19 year-old detainee, this organic revolutionary thinking was voiced to his anti-Zionist Israeli lawyer Felicia Langerwho fought against the Israeli unjust judicial system throughout her 23-year career before returning to her country of origin Germany. In her book With My Own Eyes(1975), Langer recorded her encounter with my father on 6 April 1972 in Kafer Yonah, an Israeli interrogation center. Thanks to her, I have access to my dad’s earliest quote:

“I saw how children were being brutally shot dead in the camp’s streets by the Israeli border guards. I witnessed the murder of a little girl who was just leaving her school when an Israeli soldier from the border guards shot her dead. They raid the camp with their thick batons beating up everybody. They break into houses inhabited by women without knocking on the doors. They mix the flour with oil during their aggressive inspections deliberately and without any necessity.”

The systematic oppression which Palestinians live under Israeli occupation while in their unsafe homes and neighborhood chased my father to prison. “After his arrest in Jabalia Camp on January 1, 1972,” Langer states, “they dragged him to the Gaza police center while beating him with batons all the way. They showered him with extremely cold water in winter. Meanwhile, soldiers continued to attack him with batons everywhere to the extent that he lost his sense of hearing. Langer quotes my dad’s experience of this method of torture:

“This continued for 10 days… Then they threatened that unless I talked I would be banished to Amman, where I would be killed.”

Like all other Palestinians, my father was automatically trailed at an Israeli military court, where judges and prosecutors are Israeli soldiers in uniform, and the Palestinians are always guilty for challenging the authority of the military occupation regime. According to an Israeli human-rights group B’tselem, Israeli military courts “are firmly entrenched on the Israeli side of the power imbalance, and serve as one of the central systems maintaining its control over the Palestinian people.” In other words, they are an integral part of the Israeli apartheid structures.

Besides his Palestinian identity which would have automatically proved him guilty, his

This was the first picture shot of my father Ismael in 1983 in Nafha- Negev after 12 years in Israeli jails. Due to this, not a single picture exists of my dad in his 20s.

socialist values further complicated matters. “Especially bitter is the fate of anyone suspected of holding communist values,” Langer observed. On 30 November 1972, the persecutor called the court to take part in the “serious war against terror,” in a plea upon the court to impose the harshest punishment against my father and his comrades who were charged for belonging to the Marxist-leaning Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. According to Langer, the persecutor claimed to be gentle in “not asking for death sentences.” Before announcing the multiple life sentences, the judge allowed my father and his comrades to say last words, but warned, “I don’t want to hear political speeches.” His comrade said there is no point since they did not recognise Israeli jurisdiction. Riot erupted as a result, and the defendants weren’t allowed to speak. But in the middle of all that, my father shouted his belief in “the triumphant power of the revolution.”

Despite his sentence that promised death in jail, my father believed an end to his living nightmare would come with the triumphant power of revolution!

Prisoners’ Exchange of 21 May 1985

The story of the exchange deal all started when Ahmad Jibril of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine- General Command (PFLP-GC) captured three Israeli soldiers (Yosef Grof, Nissim Salem, Hezi Shai) in revenge for thousands of Palestinian prisoners kidnapped by Israel without any apparent reason. After a long process of negotiations, both sides struck a deal that Israel would release 1,250 prisoners in return for the three Israelis that Jibril held captive. My father was included in the deal, and fortunately, he was set free at the age of 33. Among the released prisoners were the Japanese freedom fighter Kozo Okamoto who had been sentenced to life imprisonment, and Ahmed Yassin, the leader of Hamas who was sentenced to 13 years imprisonment in 1983.

My father told me the story of 1985 prisoners exchange with tears struggling to fall. “I cannot forget the moment when the leader of the prison started calling off the names to be released,” he said while staring at a painting hung in his room that my father drew during his imprisonment of flowers blooming with the names of his family among barbed wires.

Among the prisoners was Omar al-Qassim, a leading member of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP). Al-Qassim was asked to read the list of the names loudly. He was initially excited, hoping his freedom would be restored. Every time he said a name, a scream of happiness convulsed the walls of prison. Suddenly, his facial expression started to change, with reluctance to speak after he noticed that his name wasn’t included. My father thinks that this was a form of psychological torture by the Israeli prison manager. But Al-Qassim left him no chance for fun, and withdrew himself with dignity. Sadly, he died in an Israeli cell after 22 years of captive resistance, pride and glory.

My father described this emotionally-charged moment as bittersweet. The happiness of freed prisoners was incomplete for leaving the other prisoners in that dirty place where the sun never shines. “We were like a big family sharing everything together. We collectively handled the same pain and united to fight for one cause,” my father told me. “Although I am free now, my soul will always be with my comrades who remain in there.”

History repeats itself. On 18 October 2011, we experienced a similar historical event with a swap deal involving the Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who was arrested by the resistance in Gaza while he was on top of his war machine (an Israeli tank). Just like what happened with Shalit, the capture of three Israelis caused uproar in the Israeli public opinion and international media at that time, but the thousands of Palestinian prisoners behind Israeli bars were not noticed, except by the resistance groups that have always pressured Israel to meet some demands regarding the Palestinian prisoners.

The international media reaction to such events also invite anger in their emphasis on the arrested Israeli soldiers by the “terrorist” Palestinians. Thousands of Palestinian political prisoners are left behind in Israeli jails with basic rights to medical care, family and lawyer visits and fair trial are denied, and the rest of Palestinian populations endure other forms of imprisonment under Israeli structures of siege and occupation. But mainstream media chooses to look away.

My father has always said that “prisoners are the living martyrs.” He also described Israeli jails as “graves for the living.” Let’s unite and use all the means available to help thousands of Palestinian political prisoner have fewer years of suffering, especially at times the Coronavirus poses an additional danger to their lives. We share this collective responsibility. Their freedom will be a triumph for humanity.

May 25, 2010 | Categories: Palestinian Political Prisoners, Stories from my father's life | Tags: Gaza, Israeli Occupation, Israeli Occupation Forces, Israeli Prison Service, Palestine, Palestinian Political Prisoners, Palestinian prisoners, Prisoners, Swap deal | 11 Comments

I was watching a documentary report about Al-nakba Day, the day when my grandparents left their homeland by force in 15th of May, 1948. I was looking at my mother’s glittering eyes. “Are you going to cry?” I asked. “Your grandfather used to go every day to a high place in north Gaza called Alkashef Mountain. People used to see him sitting, pondering his raped homeland, Beit Gerga, and crying.” She said with that gloomy broken voice. My grandmother used to say a proverb sarcastically means that the lands are ours and the strangers fire us. She is completely right. I don’t understand how anyone could dare firing people from their lands.

Our poor grandparents thought that the immigration caesarean would be for a week or maximum two years. They were very simple and uneducated people that they didn’t understand the game that Israel and its allies played. Sadly, my grandparents died but they dreamed of return until the last moment of their lives.

I remember the times when I and my family were surrounding my grandmother listening closely to stories from her life. I used to ask her to tell us about Al-nakba every time. At first, she used to refuse complaining that she repeated that events millions of times to us. I am sure she never got fed up saying about that miserable day. She always did try to wag the nostalgia in us to our homeland which we have never seen.

When my grandparents were in Beit-gerga, their homeland, they were farmers, living for the glories of the land as every Palestinian that time. In Al-nakba Day, a ground invasion started. They became horrified. Many people from the north came running fearfully and barefoot. Huge numbers of victims died that day. One of them was my grandmother’s father. He insisted to remain home so they killed him. This was the fate of anyone who confronted them. My grandparents came to Gaza as refugees. Every single day they said “tomorrow we will return back,” but they didn’t. They died after leading that hard life and they never smelt the smell of sand again. My grandparents died but our dream of return has never died. We won’t stay refugees; we shall return.

May 19, 2010 | Categories: Reflections and memories | Tags: Aparthied, Ethnic cleansing, Gaza, IOF, Nakba, Right of return | 5 Comments

It hurts when I see the people I love bleeding tears. The only thing that comforts me is the fact, that we are Palestinians. Being a Palestinian means that we have strength in spite of injustice, hope in spite of the misery, and smiles in spite of pains.

It hurts when I see the people I love bleeding tears. The only thing that comforts me is the fact, that we are Palestinians. Being a Palestinian means that we have strength in spite of injustice, hope in spite of the misery, and smiles in spite of pains.