Art in Palestine: A narrative and mobilisation tool and a necessary means of survival

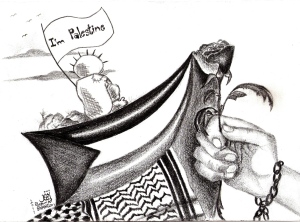

Figue 1: Reflections

Introduction

Ever since the emergence of the Palestinian cause, art has been the visual expression of the Palestinian struggle for liberation. Most visual production of Palestinian artists has been strongly tied with the political conditions that Zionist settler-colonialism brought in, shaping every facet of the Palestinians’ daily life. Palestinian artists are not exempt from these conditions. Palestinian art has mostly – but not only – reflected the Palestinian people’s suffering and state of loss and exile that the traumatic events of the 1948 Nakba caused.

The well-known Palestinian artist and art historian Kamal Boullata raised some questions regarding Palestinian art that I will try to offer a humble answer for through my drawings.

“How does one create art under the threat of sudden death and the unpredictability of invasion and siege? More specifically, how do Palestinian artists articulate their awareness of space when their homeland’s physical space is being diminished daily by barriers and electronic walls and when their own homes could at any moment be occupied by soldiers or even blown out of existence? In what way can an artist engage with the homeland’s landscape when ancient orange and olive groves are being systematically destroyed? When the grief of bereaved families is reduced by the mass media to an abstraction transmitted at lightning speed to a TV screen, what language can a visual artist use to express such grief? (Boullata, 2004)”

This piece will be a personal reflection on my life journey through the lens of my art that was mainly inspired from experiences instilled in my memory from my life in the Gaza Strip, Palestine.

Palestinian art as a narrative instrument of resistance:

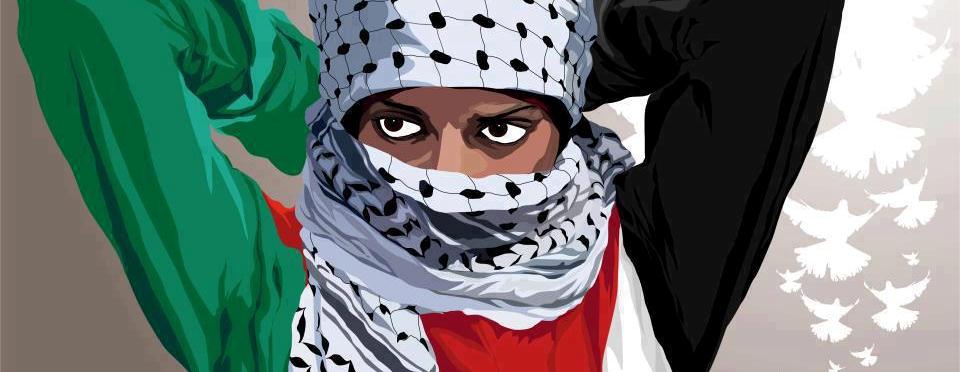

Figure 2: For the Sake of the Sun

Palestinian art, from the twentieth century up until now, has always been a visual reflection of the Palestinian struggle that aimed to depict the reality of the Palestinian people, their hopes and aspirations, their suffering, coupled with resistance. It is also a visual self-representation tool that aims to provide a counter narrative to the hegemonic Zionist misleading narrative of the Palestinian reality, to raise political awareness on the Palestinian issue and urge for mobilisation at an international level.

Speaking of narrative brings to mind the words of Edward Said, the late Palestinian exiled academic and writer, which reminds that, “no clear and simple narrative is adequate to the complexity of our experience” (After the Last Sky 1986: 6).

“To be sure, no single Palestinian can be said to feel what most other Palestinians feel: ours has been too various and scattered a fate for that sort of correspondence,” Said eloquently stated. “But there is no doubt that we do in fact form a community, if at heart a community built on suffering and exile” (After the Last Sky 1986: 5-6).

Certainly, Palestinian art has served as a narrative instrument that is used to challenge the hegemonic Zionist narrative which has been tirelessly trying to erase them. Zionism’s existence was fundamentally based on the negation of the very existence of the Palestinian people, a fact that is implicit in Israel’s fourth Prime Minister, Golda Meir’s infamous quotation that, “There was no such thing as Palestinians, they never existed” (Matar, 2011, p. 84).

I’m Palestine

Among many other forms of expression, art for many Palestinians was seen as a way to visually participate in writing their own narrative, to express their identity, to empower the Palestinians’ voices, and to move beyond the victim circle to become actors who actively, critically and creatively engage with their surrounding matters.

Over the course of the Palestinian struggle, the Palestinian people increasingly regarded every piece of art that came to reflect their living conditions in the Israeli grip as a means of resistance. Many Palestinian paintings displaying the ‘forbidden’ colors of the Palestinian flag have been confiscated, and many artists faced interrogation or even a prison sentence due their art that was perceived as ‘an act of incitement’. Let us not forget the late Palestinian influential exiled artists Ghassan Kanafani and Naji Al-Ali, whose art and literary production led to their murder.

Reflections on my artwork

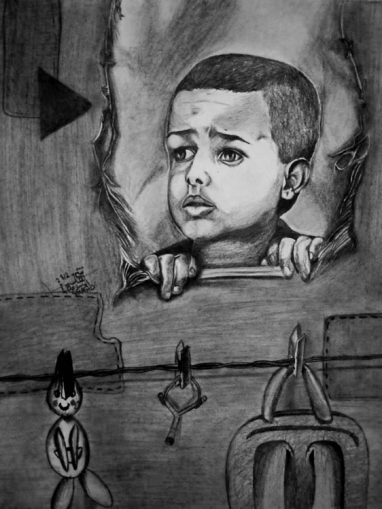

Figure 3: Children of Refugee Camps: A violated Childhood

The majority of Palestinians have become politicised due to their complex and intense political reality that shapes every aspect of their lives. I am no exception. Art for me was an expressive tool in which I found empowerment to my voice. It served as my humble tactic to overcome the state of siege and occupation imposed on us, to escape the feeling of helplessness that can be easily felt in such suppressive and oppressive life conditions that the Palestinian people endure which I was born within. It was also a tool that I used to engage politically and socially with the harsh surrounding. While living in Gaza, my art was an attempt to connect not only on an internal level as a part of the Palestinian community, but also internationally through online social networks that I used as a bridge that connects the international community with the Palestinian people’s struggle for liberation, which should be addressed as a central global issue.

Since my birth in Jabalia Refugee Camp in the north of the Gaza Strip, the biggest and most densely populated refugee camp in Palestine, I have never known what life is like without occupation and siege, injustice and horror. Like the child depicted in Figure 3, growing up in Jabalia refugee camp was the window to understanding the Palestinian reality under occupation. Art has been the way I naturally sought since a very early age to describe what I felt was indescribable.

In the context of Palestine under which people endure unbearable living conditions, creativity is a necessary tool for survival and a way towards less depression and better physical and mental health.

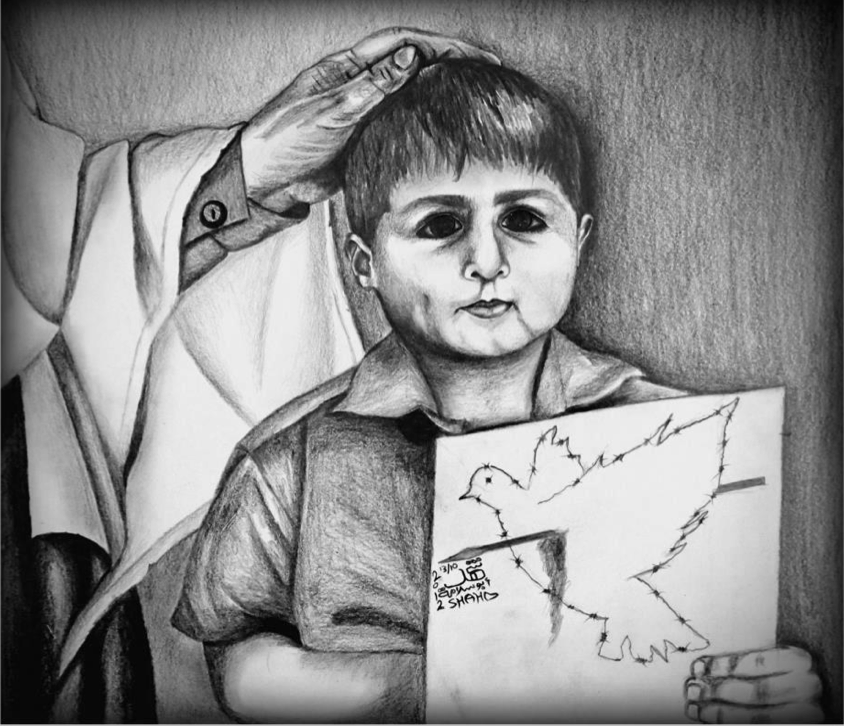

Personally, observing the Palestinian children being born in a difficult reality that subjugates them to terror and trauma at very young age was the most painful. Thus, most of my drawings are of Palestinian children whose innocent facial expressions I find most telling. Check Figure 3, 4 , 5, 6 and 7 in the slideshow below:

An ongoing Nakba:

My generation, the third-generation refugees, was already blueprinted with the traumatic events of the Nakba, which for Palestinians, is not only a tragic historical event that resides in the past, only to be commemorated once a year with events that include art exhibits and national festivals among other things. “It was never one Nakba,” my grandmother used to say asserting that it was never a one-off event that happened in 1948. The Nakba is experienced instead as the uninterrupted process of Israeli settler-colonialism and domination that was given continuity by the 1967 occupation, and which every aspect of daily Palestinian life is affected by. Growing up hearing our grandmothers recount the life they had before, the dispossessed lands that most would never see again, has formed the collective memory of the Palestinian people. My grandmother described a peaceful life in green fields of citrus and olive trees, the tastes, the sounds, the smells that remained only in her memories in our village Beit-Jirja which was violently emptied of its inhabitants and razed to the ground in 1948 like hundreds of other villages.

As Boullata described, ‘Today, memory continues to be the connective tissue through which Palestinian identity is asserted and it is the fuel that replenishes the history of their cultural resistance’ (Boullata, 2009, p. 103). Palestinian art has been always perceived as a cultural form of political resistance which often addressed issues related to collective memory, memories of the Nakba, and the lived reality of injustices and oppression endured by Palestinians under the on-going occupation with an emphasis on the people’s resistance in the face of Israel’s brutality as coupled with hope, which in itself is resistance. Art has served as a basic mobilization tool that was gradually perceived, not only by the Palestinian public, but also by the Israeli forces “as emblematic of a collective national identity and crucibles of defiant resistance to occupation” (Boullata, 2004).

Several drawings of mine, such as those featured below, were an attempt to emphasize this hope through the continuity of the struggle from one generation to another. They were my response to several Zionist leaders who assumed that time will make the Palestinian refugees forget about their right to return. The drawings come to assert that they were absolutely wrong. The old will die and the young will keep on holding the key, embracing their legitimate right to return. The key is a symbol of the undying Palestinian hope that return is inevitable. The young generation is perceived as those who will carry the burden of the cause and continue the struggle that the previous generation started until freedom, justice, equality and return to the Palestinian people. Thus, Palestinian children became the symbol through which “We nurse hope” as Mahmoud Darwish said (Darwish, 2002).

From an early age, drawing was not only a tool of expression, but also a way to convey a political message, to call for mobilisation in support of the Palestinian struggle. The power of art lays in the fact that is a universal language to communicate the unspeakable that many people in safety zones cannot fully understand. With the availability of online platforms, it became possible to reach beyond borders and checkpoints to a wider audience.

I was only nine years old when my parents noticed my drawing skills that were limited to black warplanes, pillars of smoke in the sky and crying eyes. This coincided with the eruption of the second intifada in September 2000 when I used to accompany my mother and aunt to the martyrs’ funeral tents to offer our condolences. I used to hate the green colour, as it was associated in my memory with martyrs’ funeral tents, which were disturbingly visible in Jabalia refugee camp’s landscape. The first poem I ever learned to memorize by heart was one by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish entitled, “And He Returned …In A Coffin”. As a nine-year old girl, I stood in front of everyone sitting along the benches in the marquee, looked into the people’s tearful eyes, and in a powerful but shaking voice, I recited,

They speak in our homeland

they say in sorrow

about my comrade who passed

and returned in a coffin

Do you remember his name?

Don’t mention his name!

Let him rest in our hearts.

Let’s not let the word get lost

in the air like ash.

It was moments like these, during the tumult of the second intifada that fundamentally shaped my consciousness about the land and my place in it. Since childhood, the scenes of war, the faces of martyrs, the injured and detained people, the cries and weeping of the martyrs’ relatives over the loss of their beloved, have been chasing me day and night. These scenes pushed me to seek art as a way to express my emotions, to reconcile with my wounds, to reflect on my memories and experiences that many Palestinians share.

Humanising Prisoners’ issue through art

Chains Shall Break

Moreover, being a daughter of an ex-detainee means I have grown a unique attachment to the plight of the Palestinian political prisoners, not only from a political perspective but also from a personal one. My father spent a total of fifteen years in Israeli jails, a part of his original seven life sentences. The stories of resilience, suffering and oppression that I grew up hearing from him about his stolen youth in Israeli jails have made me develop a particular passion to advocate for justice for Palestinian political prisoners who endure inhumane living conditions under the Israel Prison Service which denies them their most basic rights.

However, in spite of its importance, the issue of Palestinian political prisoners and their families who suffer immensely from the pain of longing and separation and are often denied their right to family visits is not given the deserved attention in the political arena. They are not only marginalized, but also dehumanized as whenever they are mentioned in the media discourse, they are mentioned as merely statistics or numbers. Through the drawings below, I attempted to humanize the prisoners’ plight and draw attention to their daily resistance in the face of the oppressive Israeli jailers that treat them as if they are not humans. I tried to depict their determination to break their chains, their resisting spirit in Israeli jails. I also tried to express their families’ pain as they are imprisoned in time, waiting for a day when their re-union without barriers in between will be possible again.

The Pain of Waiting: Imprisoned in Time

This drawing above was an attempt to show how waiting for a reunion between the prisoners and their families is in itself a torment. My mother experienced seeing my father being violently captured in front of her eyes from the middle of their house three times when the first intifada erupted in December 1987. She was a newly married bride expecting her first child, my eldest brother Majed, when he was re-arrested and forced to serve an administrative detention order, an arbitrary procedure that Israel uses against the Palestinian people to imprison people without charge or trial, usually based on secret information that neither the detainee nor his lawyer have access to. The experience was repeated when my elder sister Majd was born, and lastly soon after my birth. My mother has always described the torturous experience of waiting for my father’s release, how she spent days and nights staring at the clock, waiting impatiently to hear some news from him while her right to family visits was denied.

The imprisonment experience repeats itself hundreds of thousands of times across Palestine, regardless of gender or age. I have many family members, friends and neighbours who experienced unbearable conditions that range from physical torture to psychological torture to even sexual torture. Palestinian political prisoners have always resisted the brutality of the Israel Prison Service. They have no weapon but hunger to protest their inhumane living conditions and call for their right to proper medical care, the right to family visits and other basic rights under international law while imprisoned. “Hunger strike until either martyrdom or freedom” is a motto that many prisoners adopted. The drawing below aimed to illustrate the spirit of this motto.

Hunger Until Either Martyrdom or Freedom

Memories of War

The turning point of my life was at the age of seventeen, after witnessing the 22-day massacre that the Israeli occupation forces committed against our people in Gaza in 2008-09. During that dismal period when we remained in darkness amidst the continuous bombing, destruction and mass killing of Palestinians in Gaza, I had a terrible sense of being isolated from the rest of the world. The trauma of seeing such levels of brutality was intense. No one was certain if they would live for another day or not.

One of the most memorable moments is that when one night, I was sitting in darkness, surrounded by my mother and siblings in one small room of our house under one blanket. No voice could be heard, just heartbeats and heavy, shaky breaths. The beating and breathing grew louder after every new explosion we felt crashing around, shaking our home and lighting up the sky. Then suddenly, the door of our house opened violently and somebody shouted, “Leave home now!” It was my dad rushing in to evacuate our house because of a bomb threat to a neighbour. I remember that my siblings and I grasped Mum and started running outside unconsciously, barefoot. For three days we stayed in a nearby house, powerless as we sat, waiting to be either killed, or wounded, or forced to watch our home destroyed.

This merciless and inhumane attack killed at least 1417 men, women and children. I wasn’t among them but what if I had been? Would I be buried like any one of them in a grave, nothing left of me but a blurry picture stuck on the wall and the memory of another teenage girl slain too young? Would I have been for the world just a number, a dead person? I refused to dwell on that thought. Many drawings of mine, such as those below, were inspired from memories attached to this traumatic event whose memories always floated back whenever an attack was repeated. Most importantly, resorting to art was a necessary means that helped me preserve my sanity and overcome harsh traumatic events that I experienced throughout my life in the suffocating blockade of the Gaza Strip.

Conclusion

While living under conditions of ghettoization, occupation and military assault, a continuation of the Zionist domination of the Palestinian land that was dispossessed in 1948 for the ‘Jewish state’ to be founded, Palestinian artists continue to be driven to express themselves in paint, photography, and other visual media, with having the Palestinian struggle for liberation as the central theme for their artwork. Art has offered Palestinians a platform to engage with the politicaly complex reality and express the suppressed voice of the Palestinian people in visual forms that can communicate universally. It was also a way to humanise the people’s suffering that is usually dehumanised in mainstream media and reduced to a dry coverage of abstractions that present them as numbers and statistics. Palestinian art, therefore, has been perceived as a form of political resistance, a mobilization tool, a way to assert the Palestinians’ embrace of our legitimate political and human rights, such as the right to return, the right to self-determination, and the right to live in dignity and freedom.

A heart rending message. Beautifully expressed. A passionate reminder to those readers in the West that it is our indolence and for some their support of Israel that allows this intolerable situation to remain. We are shamed and should support the Palestinian cause.

LikeLike

May 15, 2016 at 1:10 pm

Thanks John for stopping by and reading this! Glad you enjoyed it. Keep up the hope. the International solidarity with Palestine is absolutely growing. Best, Shahd

LikeLike

May 16, 2016 at 4:51 pm

Thank you for sharing a life that I have always been grateful my children were saved…. I hold you in my prayers, for what is worth.

LikeLike

May 15, 2016 at 7:17 pm

This text is awesome. You are a wonderful person abd I think I met you at Rafah border in summer 2009 (we were in the international camp to demand the end of the siege) You were going to Cairo and had a brief stop and we talked so much in 10 minutes or so. It was so short a time that I did not even ask you your name, but I am quite sure it was you.

Since then I have been wanting to meet you or at least to be in touch (by e-mail), but I never managed to have your address.

Anyway, what I just wanted today is to ask you if you have read “The Blue between the Sky and the Water”, by Susan Abulhawa ? This novel is the perfect illustration of what you wrote here, especially about humanising the people’s suffering, etc. It actually is the best novel I have ever read. If you have not rade it, pleae do it and I am sure you will advertise for it, then.

All the light and the love for humankind, justice and freedom

Chris

LikeLike

May 16, 2016 at 11:34 am

Hi Christian, thanks for your lovely comment. Maybe that person was me and maybe not, but regardless, nice to meet you! I haven’t read the novel, but it was on my list of books to read! I love Susan Abulhawa and I had the honour of meeting her in Gaza when she was part of Palestinian Literature Festival. My email is sh.abusalama@gmail.com. All the best, Shahd

LikeLike

May 16, 2016 at 4:49 pm

This is truly a beautiful piece. The way that you not only explained the art, but also meshed everything together and were able to show clear links and themes, was pure art of its own. Weaving in your personal stories – especially those from your childhood – spoke to me, and you are truly an inspiration.

I wrote a very brief piece on Palestine-related art and my personal ties to them. Check it out and I would love to hear feedback as I develop my blog! Here is the link: https://palestineroots.wordpress.com/2016/09/11/art-and-the-wall/

Thank you for posting this!

LikeLike

September 28, 2016 at 12:34 am

Pingback: Arte en Palestina: Una herramienta de narración y movilización y un medio necesario para la supervivencia - Desinformémonos